“Whatever you do will be insignificant, but it is very important that you do it.” – Mahatma Gandhi, Indian nationalist and civil rights leader

July 7th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

July 7th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

July 7th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

While I was finishing Monday morning patients in the clinic and seeing my inpatients off and on as time permitted, I got a text from Isaac. The driver had been able to get past the roadblocks on the highway to la Ceiba and would arrive in about 45 minutes to pick me up and take me directly to the ferry terminal. Waiting in the town of La Ceiba seemed like a poor idea as the demonstrations against the impending privatization of health care and public education often closed major streets and highways around La Ceiba. They also involved some small fires. Not having time for one last delicious lunch at the “comedor” in the hospital was a downer. The possibility of getting past the roadblocks in early afternoon was the plus side.

So what is good about leaving Hospital Loma de Luz? First of all, it’s an established healthcare facility with ongoing care that will continue just fine when I leave. My role was essentially to learn and to be a relief worker so their regular docs could take short breaks. Patients will continue to receive excellent care, but I’d like to think that Isaac and Jason will miss me just a little when the radio blasts them from sleep during a night on call for the ER.

Leaving patients with ongoing unstable medical situations is always hard for me, even though coordinated care with the two “local” live-in American doctors was arranged. What will happen to:

Saying goodbye to hospital staff had to be done quickly, and some of the goodbyes were by text messages a few miles down the road as we sat at the newly replaced roadblock of tree trunks and tires between Balfate and Jutiapa an hour later. Conversations with the young protesters were friendly and never threatening. They moved some logs and tires to allow me to pass through with Sergio, a great driver who got me to the ferry terminal about three hours early. On the way Sergio and I talked about the similarities in our childhoods on farms and about our pride in our children. Waiting near the ferry terminal was pleasant, and there were plenty of food stalls in the neighborhood where I could snack and watch life go by, including the wealthy coming to buy ice for their boats, the linemen working for TIGO telephone company stopping to buy baleadas (really great meat or vegetable filled pastries like you might find in most countries around the world) and the 6 and 8 year old brother-sister pair who counted the crayons in the 64 Crayola box and colored in their new coloring books. They tried to convince me that they had 75 different colors, but those boxes haven’t changed much in 60 years; they still have multiples of 8 in the copycat yellow and green Crayola boxes. This was a 64 crayon box just like one of my fortunate classmates (with a wealthy relative) brought to Marquette Grade School 4th Grade class in the fall of 1960 when the rest of us made do with 16 colors. Arguing with me about the number of crayons in that box would have been equivalent to arguing with me about which set of beautiful fins defined a 1959 Chevy as opposed to the slightly softer fins on the 1960 Chevy. You’ll lose that argument. Argue with me about religion or politics and it will be much more satisfying and less likely to lead to bloodshed.

So, what did I learn at Hospital Loma de Luz? I learned that in that small jungle hospital, the amount of good care provided to that community (or the bang for the buck) would probably supersede what we are able to do in our beautiful and well-loved hospitals in our small towns of Kansas. That’s saying a lot.

I learned again how much I still need to learn about providing good health care with few resources. The INMED course was designed to open our eyes to that dilemma. Working at Hospital Loma de Luz certainly gave me a chance to put into practice some of the concepts from the INMED International Medicine and Public health courses. I also saw an impressive determination and compassion in the hearts and souls of the small physician and nurse volunteer population who are the backbone of the hospital and who constantly teach the people around them as they work at Loma de Luz. In hot hallways with seemingly no movement of air late at night as we waited for a test result or for another patient to arrive, I listened to stories of how these few brave people made the decision to spend years at this isolated hospital in the jungle of the Colón province of Honduras and how they find purpose and happiness in what they do as they struggle to find ways to keep a spouse or teenage children feeling safe and thriving in this slightly hostile environment. The person who is working there daily doesn’t have a lot of time to think about the realities and dangers of daily life in the jungle with political strife and violence just down the road; work beckons and demands immediate response. The spouse of the doctor or nurse, who live up the hill in a pretty decent house with electricity, safe running water, a washing machine and a big refrigerator still aren’t living in a typical “neighborhood”. There aren’t many peers or neighbors. It’s tough. Their idea of how to serve “the forgotten” might not match up with that of the medical parent.

And what else did I learn? Those books by Drs. Tom Dooley and Albert Schweitzer from over fifty years ago described situations that weren’t much different from what I saw at Hospital Loma de Luz. Political conflicts still were just down the road or over the hill, but seemingly less threatening than in Dr. Dooley’s books.

Best of all, I was correct in my very basic assumptions all those years ago as I read those books on a farm in rural Kansas:

Some photos of my last 24 hours in Honduras, as I traveled by ferry to the island where I’d meet my flight home.

Back in Alaska.

“Whatever you do will be insignificant, but it is very important that you do it.”

– Mahatma Gandhi, Indian nationalist and civil rights leader

June 29th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

There has been a gap in my blogging for lots of reasons, but last weekend hospital and ER “on call” duties could be blamed for most of it. I scribbled notes and found myself overwhelmed by the scope of conditions that presented to the hospital.

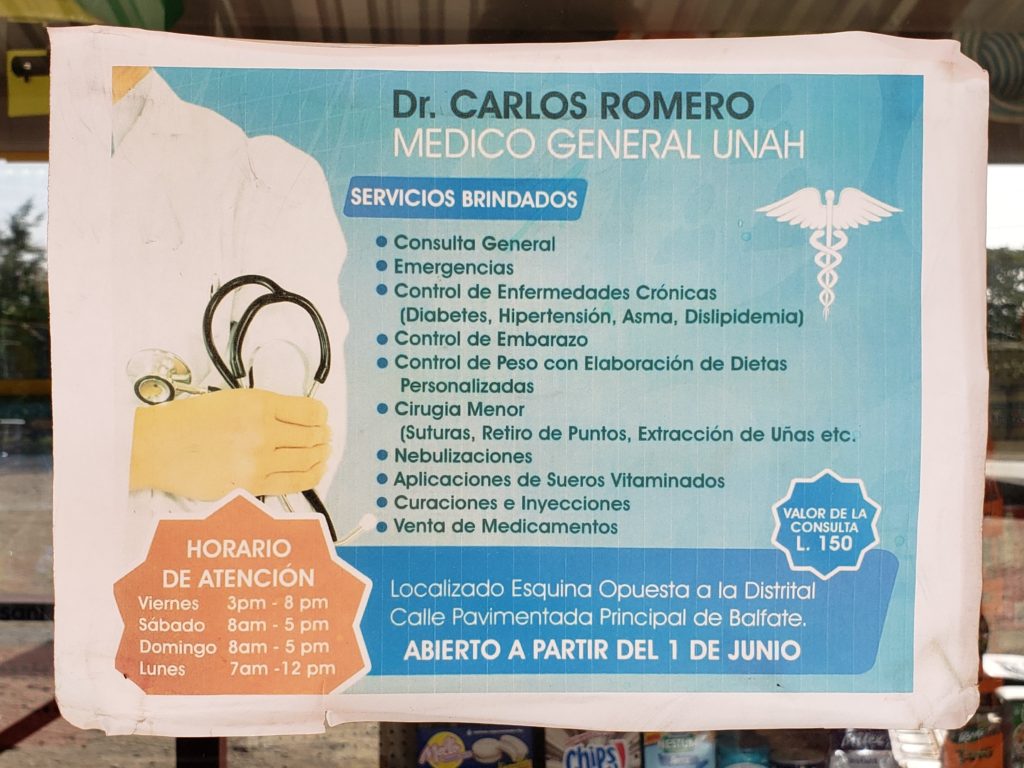

On Friday afternoon, anticipating the long weekend ahead, I hitchhiked to Balfate for a “last break”, riding with a nearly toothless old fellow (probably my age) in his beat-up pickup with the plastic coating on the windshield being the main source of support for that broken piece of intended protection. We talked about weather and the dry spell and how it affected the crops. Wait….was I in the Colón province of Honduras, or was I in McPherson County, Kansas? He dropped me off at the intersection for the road going into Balfate, and I walked the short distance into town. Strolling around on the deserted beach and watching the big waves while observing the Friday night over-imbibing of the bar/restaurant patrons on the closest bar to the beach, gave me an insight into the social options here on a Friday evening.

After buying snacks in little “pulperias” (neighborhood grocery kiosks that have the important stuff) along the way, it came time to go home, and I found myself back on the highway watching every vehicle closely for an empty seat while chatting with the motorcycle repairman. Under his roof supported by a couple of poles along that busy dirt road, he had multiple motorcycles stripped down to the frame, and motorcycle parts and chains were hanging in an orderly fashion all over the place. He probably had any replacement part one would need for a breakdown in Balfate. Finally a motorcycle with a scrubbed up “Friday going on a date” young guy (who really smelled good, too) stopped to give me a ride. It turned out he was the guy who manages the security cameras which are all around the Loma de Luz compound. As I rode home without a helmet or any kind of protection, I understood some of the risks, and wondered if I would have been better walking the four miles on that nice evening. He seemed skilled at dodging the potholes and loose sand, and he delivered me to the gates of Hospital Loma de Luz a few short minutes later.

I mention my thoughts on the motorcycle, because after a steady but really pleasant weekend of watching the inpatients, dismissing a couple of hospitalized patients, handling minor emergencies/urgent care type situations and talking to Isaac and Carolina about the ultrasound on a woman who presented with pregnancy problems (triplets, with one having anencephaly – no head), I spent my late Sunday afternoon, evening, and night in the emergency room with motorcycle accident injuries. All evening, I thought about twice having been the passenger on a motorcycle on our rough road without the protection of a helmet or long trousers.

Let me set the stage. It’s only 93°F/33.8°C outside, but the heat index is 106°F/41.1°C. Inside the emergency room and the surrounding hallways, the temperature had to be nearly identical, but with the added body heat from four ER patients (a 3 bed ER with another cart rolled in), at least 2 (more often 4) family members for each patient, plus the heat generated by a sweaty foreign doctor (name withheld, but can be identified by this blog) who felt unprepared for what was unfolding, the temperature was not to be measured by a thermometer. In three of the four beds, there were people who were involved in separate motorcycle accidents. In the fourth, was a poor fellow who had the misfortune to be hit by a car. His left leg x-ray looked like the bone grinder in a crematory hadn’t finished its job.

He had been in a hospital in the city of San Pedro Sula for six days, but family was concerned that he hadn’t seen a doctor since admission, so they decided to make the four hour drive to see the people at Hospital Loma de Luz. After I used WhatsApp texting application to send a copy of his x-ray to the surgeon, he agreed to take care of him after I got him admitted to the hospital.

Then with a quick radio call and texted image of the fracture shown below, Isaac, my sponsor, took over with the stoic 14 year old girl whose forearm was bent into a half-moon curve from falling down a river embankment.

His skills at sedating her and reducing the fracture were apparent. My job there was easy – hold the arm in correct position while he did the casting after the fracture reduction. I felt less lonely now with two of the four “accidentados” already part of a long term plan that didn’t require much from me.

The other two patients were a little more complicated. Both had gone down on their motorcycles on the sandy roads, and their injuries consisted of head contusions, less problematic fractures, abrasions all over, and lots of lacerations, some of which became apparent only after the next patch of dried blood was cleaned up. Without a nurse in ER, I was on my own to find each needed item to take care of these guys– sutures, local anesthetic, instruments, and casting material. Just a hint in case you are ever in this situation: No matter how many packets of clear suture you find in the right size, don’t use it. Keep looking until you find black or blue suture. Your life and the patient’s life will be much easier. Believe me on this. I was pretty overwhelmed when I allowed myself to think too much, but the reminder that “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step” kept me focused. If you happen to be going on that journey and the heat index in the ER is 106°, be sure to keep drinking lots of water. I’m sure Lao Tzu couldn’t get that little bit of advice into the sentence without ruining the flow of the words that made him famous.

Over the next couple of hours lacerations were revealed and repaired. None were complicated, but they were numerous. X-rays were taken and interpreted and then shared by sending the images via text to Isaac or to Jeff, the surgeon. An interesting feature of the ER at this hospital is that the bays are theoretically separated by curtains, but they don’t partition well, and the heat necessitates keeping airflow from the ceiling fans and open windows shared by not obstructing it with curtains. As I moved from patient to patient repairing lacerations**, my retinue moved along with me from one ER bay to the next, watching and quietly supervising. The creator of HIPPA regulations would have had a stroke while observing this pattern of “experience sharing”–and then I really would have been busy with one more admission to the hospital. Finally the chaos settled down around 10:00 p.m., and I saw an opening to run home and eat the rice, cheese and orange bell peppers that had patiently waited since lunch time. It was hot and dark, and I was hungry and thirsty, but I stepped onto the first of the suspension walking bridges with a fierce confidence of having survived a rough evening—so far. And I just dared a howler monkey to swoop down and surprise me as I headed toward my main goal of food and eventual sleep. At that point I was almost in a delusional state of believing that I had the power, if not the energy reserve, to grab him, butcher him, and have him on the barbecue grill before midnight.

** Not once did a patient ask me how many stitches I was putting in or when they had to be removed.

June 23rd, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

A few days back I ended my blog entry with a teaser about my bus trip to La Ceiba. Unfortunately I don’t have many photos about the “bus” part of it.

After a short pre-dawn nap without an ER call or hospital call for over two hours, I discovered that my radio was at the wrong frequency. No wonder I had been allowed to sleep for two hours. New lazy foreign doctor turns radio to wrong frequency and gets to sleep. Good trick. I showered and hurried to hospital, but they hadn’t called me, and my guilt and shame was relieved.

Quick 6:00 a.m. hospital rounds, checked out and turned my patients over to Maria, who would be on call for ER and inpatient, plus OB (she’s tougher). Put on some really fancy clothes – long pants and a polo shirt, and headed down to the road to catch the “special bus” to La Ceiba to run some urgent errands and to buy a few food items. I wasn’t sure why two of my colleagues weren’t there waiting along with me — we had planned this all week — but the guard said the bus had already gone. I waited along the road, and soon another bus came along and I was on board. I had been concerned about no knee room on the bus to La Ceiba – about a two hour ride – and I had imagined the discomfort. No worry here about knee room anymore. Seats were taken and the aisles were packed. I actually clawed my way through the crowd and got a place to stand in the aisle. My knees were just fine standing there, so my concern about tight seating was unnecessary. I steadied myself as we went along the dirt road dodging potholes and rocks, and I grabbed the parcel racks that were attached to the bus roof with strap iron. At the location where I was hanging on (tightly), the strap iron holding the racks was actually attached to the roof on both sides of the bus. Farther back, it was less stable; in other words the bolts were missing or loose. I just kept looking at each rack, wishing that I had a 1/2” wrench for one side and a 9/16” wrench for the other. Tightening those bolts would have made me feel more secure while standing there unable to see out the windows (they were at about waist level). After a little more than an hour of feeling sorry

for, and admiring the imagined stamina of, my missing colleagues who obviously had taken an earlier bus instead of waiting for me, my big turn came. Half the people got off of the bus in the town of Jutiapa, and I had a seat. I finally got to experience the previously imagined problem about a place to put my knees and the legs attached to them. The vendors came aboard in Jutiapa, and with the aisle free of standing passengers, the vendors with animals, drinks, food, and clothing passed through the aisles loudly proclaiming the benefits of buying their product or contributing to their charity. Sitting was so much better than standing on that old U.S. school bus given a second life in Honduras. It was a rough ride, but I thought that I had to be at least as sturdy as my companions, and if they took this bus to La Ceiba and bragged about it, I could do it, too.

Getting off the bus in La Ceiba, I ran into a Honduran hospital lab worker who recognized me and asked me why I didn’t take the “nice bus” from the hospital. I told him that I had tried, but that the guards “insisted” I get on the bus that stopped in front of the hospital gate. He told me to go to La Colonia grocery store at about 2:00 p.m., and I’d find my coworkers and the “nice bus” home. Errands were accomplished in about one hour, and then I had several hours to wait.

Coffee in the mall, chats with multiple pharmacists in their pharmacies, cruising hardware stores and a search for a good lunch filled my free hours. As I was eating some lunch and talking to my dad on the phone at a stand next to La Colonia grocery store, here came Decca and Carolina, fairly surprised to see me. They told me how they had made the bus driver at the hospital wait while they went to my room to try to wake me because they knew I intended to be on the bus. They had gone above and beyond the call of duty in trying to find me to get on the “nice bus”, and yes it was a “nice bus”. We agreed to meet at 3:00 p.m. for the trip home, and I had enough time to buy groceries and a high-priced frozen coffee drink. Oh….and that one can of beer that I had to take outside behind the shopping center and drink while hiding in the shade of the trashy motorcycle employee parking area. My fellow workers, who came here to work with Samaritan’s Purse and other evangelical organizations, didn’t need to see me trying that beer which is prohibited on any property owned by the foundation running the hospital. I don’t break their rules.

Riding back to Balfate and the hospital on the nicer bus was a dream, relatively speaking, and we laughed about them feeling sorry for me missing the trip and about my unnecessary admiration of them and my being in awe of their toughness in riding the “local” bus to La Ceiba—which they had never done. Turned out that I was the only one who had been foolish enough to do that. The hospital bus was free, and I’d paid 40 Lempiras (about US $1.60) for my ride, believing that my suffering was being rewarded with a cheap bus ride!

I’d still prefer my amusement-park-worthy ride to any Disneyland ride. I’d rather bounce on that bus than stand in line at Disneyland ever again.

June 21st, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

It’s easy for those of us from more affluent or high resource countries to feel that because we have more access to money and material things, we must also be smarter. Of course we know better than that, but we need to be reminded. When the very poor mother brings in her child or comes on her own behalf to an appointment and describes clearly what tests have been done, what dose of medication she has been taking, or her very clear understanding of how a certain disease process affects the platelet count of her child, I’m just blown away by my own ignorance and prejudices once again. Or when I ask about previous lab tests, and a patient pulls up a PDF on his smart phone of the recent CT scan from a clinic in Tegucigalpa, I remind myself again that “poor” doesn’t mean “uninformed”. I need to remind myself of that more than occasionally.

Having potable water in every faucet on the hospital compound, lots of natural light in the hospital hallways and plenty of electric outlets and ceiling fans makes almost everything else we do easier, or even possible.

Charts here have handwritten names – each patient has four names which are often out of order and misspelled (I have to look up that word almost every time). This morning, one teenage patient had his name spelled “Andrs, Andrés, and Andress” on different pages of his chart. Going to the waiting room to call in the next patient can be similar to a comedy routine, with the foreigner overheard by at least forty people. But, the discovery of a copy of the birth certificate or national ID card in the back of every chart gave me a new way to get the names straight and practice before going out to the crowded waiting room. Now I step out there and confidently let “Gareth Gonzalo Gutierrez Gonzales” roll off my tongue in a loud voice as easily as if I were calling out to an old high school classmate.

I didn’t realize how much I missed speaking Spanish every day. Contact with the language in the form of text messages, a newspaper or music, several days a week on my phone is fine; but using it to talk with patients, joke with colleagues, while hearing the familiar sounds and seeing the familiar mannerisms and ways of Central America has brought back something that had been missing. It’s been a lot like “going home again”.

Patients often tell me that they’ve used “natural meds” before they finally give in and come see us. I’m not sure what “natural” means in these cases. Those medications usually cost about twice as much as what is prescribed here and they are manufactured and packaged just like every other product we buy. We’re the last resort, not the first choice.

It’s not uncommon for patients to arrive in the ER in the middle of the night with copies of their ultrasound and CT reports and lab tests and handwritten referral letters from other facilities. It’s a rare night that someone doesn’t show up in the ER with an IV in the arm and connected to a bag of fluids, carrying reports and telling of having had a major surgery the day prior in a city hospital. They travel like this on a bus, a motorcycle, the back of a truck, or maybe in a car from places 2 or 5 hours away with their abdominal pain, broken bones, surgical wounds and untreated cancers. Evidently the country’s hospitals are in poor condition right now with lack of supplies and personnel. The ER doc (that would be me half of the nights) then becomes the consulting physician for these people, and they have to be admitted. This was/is way beyond my comfort zone, but I’m not here to be comfortable. We still have to provide quality care to the best of the ability of the medical staff and hospital facilities. Thankfully, there are two (plus one half time) incredible family medicine docs and two incredible surgeons here. I get on the radio, wake someone up, and they always jump right in and talk me through these situations and then take over their care in the mornings if they require further surgical management. They have no fear of tackling the toughest cases if they know that there is no one else who can better handle a particular case. If I had to be isolated somewhere in the world and could have only two physicians with whom to work or to care for me or my family in the toughest of situations, I’d want to be in close proximity to any two of these people. Late at night in the hot hallways or nurses’ station with poor lighting and patients’ family members sleeping on mats on the floors, we discuss cases and listen to each other’s opinion, and we come up with a plan. If we’re really tired, we find chairs and make the discussions last even longer. This kind of collaboration allows the best use of scarce supplies and precious staff time to achieve the best outcome possible. This really is a full service hospital, and I have such admiration for the people who work here and teach me so much every day.

Mangoes falling on a tin roof overhead can send out quite a ringing sound. All day. And night.

This afternoon, an elderly lady offered to go to the cafeteria and buy me a cup of fruit when she noticed that I wouldn’t be getting to the cafeteria during typical lunch time. I was able to thank her and decline by letting her know that I had a long break coming up after the next patient. What a truly generous offer. And one of her main complaints was a painful ankle!

Latin American culture and ways of doing business have been seeping back into my consciousness here at Loma de Luz Hospital. Yesterday I needed instruments for toenail removal, and I searched several places around the clinic, ER, and hospital, and finally went to the instrument sterilization room where no one knew me. “No. None of those things available here.” We talked awhile about work and life in general, made some jokes, laughed, and made no pretense of being in a hurry—after all, that digital block in the patient’s big toe would take about fifteen minutes to really take hold. Suddenly a big Rubbermaid tub of sterile instruments appeared so I could search for what I needed. This is a little ritual in Latin America that I recognized several times since I arrived here, but I hadn’t had the need to stop and chat in Central Supply yet. Now I’m fairly certain that future instruments will be forthcoming. It takes time. There’s no real way to hurry these interactions. A few minutes chatting in the pharmacy, nurses’ station, reception desk, and about any other department pays big dividends. We see each other as humans, and then we work together. Speed and efficiency aren’t the first goals.

Wow. This has been random. Were you not warned?

June 20th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

Most of the time here is spent working in the clinic/hospital/ER, washing clothes (change often in this weather) and preparing food for the next day, but there is time to watch geckos on the ceiling at night and have breakfast on a patio outdoors watching parrots in the trees. The outdoors is real; it comes indoors, too.

June 19th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

June 18th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified ten of the biggest threats to global health. In preparing to teach a class at the hospital here in Honduras, it seemed more relevant to share these global health concerns rather than watch eyes roll as an outsider gives another class about the proper way to take a blood pressure or to wash hands or to manage simple fractures. There are no simple solutions proposed here – just observations and facts. We have to educate ourselves and listen. People who have a medical service to sell might not agree with the WHO, but it’s likely that their observations about our big threats are actually pretty much spot-on.

“Global Health” includes all of us in our spacious homes in rural and suburban Kansas or California or in apartments in New York and Alaska. These threats aren’t confined to the “third world” or “low resource” countries as we are prone to believe. We all live in this world and share the air, the oceans, and the pollutants that move around the world easily.

Three of the big ten threats to global health that are the focus of the WHO and their partners in 2019 are clearly applicable to situations I faced just yesterday and today at Hospital Loma de Luz in the Colón province of Honduras (and also face in Kansas and Alaska to some degree):

Antimicrobial Resistance

Five year old Rudy Gareth Gonzales Guevara (let that slightly altered name roll off of your tongue a few times) was here for a consult regarding tonsillectomy. Mother had been told that he needed tonsillectomy. She treated him every few weeks for tonsillitis with an antibiotic purchased without prescription at a local pharmacy. The diagnosis of a bacterial infection had never been confirmed, but he was now taking a fourth generation cephalosporin antibiotic costing the parents about $34, a huge sum here. He’s had multiple courses of mother-prescribed antibiotics, but possibly no bacterial infections. Antibiotics have saved millions of lives. But worldwide we’re seeing organisms resistant to multiple antibiotics. WHO predicts that by 2050 (not far away) we might be more likely to die from simple infections which are resistant to antibiotics than to die from cancer. It’s a global problem that will have to be addressed globally. Oh…and back to Rudy. His tonsils looked great. Grandma and I both talked to mother about bringing him here for an exam before he is “mom-treated” in the future. And grandma and I both agreed that he should stay away from a surgeon for now–and I really admire surgeons.

Dengue

As the world warms up, the geographic area of world at risk of contracting dengue, a mosquito-borne illness, continues to increase.

Last night in ER I saw my first case of Dengue, in a 25 month old child who had two days of febrile seizures. Treatment will be acetaminophen (Tylenol), and he’ll probably do well. They stayed in the low cost “Samaritan House” here last night rather than make the 2.5 hour trip home in the middle of the night. I saw him again in the clinic today before they made the trip home. This made Dengue real to me.

Strategies to control this will need to be global. It’s not going to hit Kansas or Alaska anytime soon as a major cause of death, but it will keep moving north from the tropics. We all have a stake in this.

Weak Primary Health Care

This most basic of problems continues to worsen in all countries that don’t have a strategy to bring primary health care to the majority of citizens. This includes the USA, my home country, and Honduras where I’m working this month. Bypassing primary care, and treating conditions when they are already advanced is just more expensive, even if one forgets the human suffering part of the equation. While the excellent secondary and subspecialty care that we all treasure and depend upon in both the developed and underdeveloped part of the world is a necessary part of health care, the provision of primary care services to the whole population reduces health care costs and reduces human suffering. Oh, and it also makes for a healthier population. Many countries have systems in place to make access to primary care available to almost everyone. Unfortunately my native country , the USA, does not, and the increasing cost in productive days of life lost to illness and conditions which could have been prevented will keep us from achieving full human potential. We won’t be able to compete economically with the remainder of the world. Countries which haven’t achieved good access to primary care will need to learn strategies from countries which have been more successful in bringing primary care to their citizens. Many models, all imperfect, have been tried, and some have been quite successful.

Here in Honduras today (less than one hour ago) I saw a walk-in patient at the hospital with a complaint of feeling dizzy and tired. He was 76 years old. He was fairly certain that the last time he saw a doctor (if ever) was when he was a young child. He’s had no primary care and monitoring. He was actually quite strong, and he swings a machete all day for a living. He looked pretty good, and he might be the one who actually should stay away from us! The poor guy was lost in this rural hospital and this fairly advanced health care system here in the jungle. There are health posts and doctors in this area of Honduras, and there is transport by road to those health posts, but the number of primary health care workers isn’t enough to support the population. This is exactly what we face in much of the USA now. And we aren’t even in a terribly remote area here near Balfate, even though it feels like it when the 2 hour trip to La Ceiba takes 5 or more hours because of roadblocks and burning tires from the almost daily protests on that road.

So those ten urgent threats to global health were interesting reading last month. Today they’re more real, and if I’m objective in looking at this, they don’t just apply here in Honduras. Again, don’t let yourself think for a minute that we aren’t all in this together. Well…if today is your birthday, or if you have a big test tomorrow, or you’re preparing for a big family gathering, go ahead and study or have the party and don’t think about this until tomorrow.

June 17th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

The suspension bridges are a lot of fun at 2:00 a.m. coming home from ER. It’s really dark. And I’m fairly sure that I’ll be jumping off into the dry shallow canyon below if one of those howler monkeys suddenly appears in a branch overhead and starts to roar at the wrong time.

All those years ago when I was working and studying in various places in Latin America, I didn’t dream of the miracle of the communications and connections we now enjoy. I pretty much left Kansas and mailed a postcard at some point, and then returned. What happened in between was not well recorded. But this week, while seeing such advanced cases of “everything”, I needed (and received) some encouragement from fellow medical/nursing people from my immediate family/friend circle.

I’ve received “text message encouragement” and advice from Federico, an ophthalmologist friend in Córdoba, Argentina, who understands work in low resource areas of the world and travels to Fiji regularly with an eye surgery team. I can text him as I work in this remote Honduran hospital, and he works in his practice in Jesus Maria, Argentina.

I’ve also been texting to describe the serious cases and lack of resources to a young mother and physician who grew up in our house. At age 16 Kayt acted as a medical interpreter for Nancy and Elliott, my former med school classmates, when we worked in Honduras after Hurricane Mitch more than twenty years ago in lieu of attending our 20 year med school reunion. Who would have dreamed that we could be texting medical information back and forth in a matter of seconds with her in the position of a family practice doctor who understands what I am doing here? And Rachel, the baby in our family, now understands medical/nursing jargon in her role as a last year nursing student. She successfully worked two years under conditions much more challenging than these, and she is my other “go to” stress reliever. We all need someone who truly empathizes with any given situation, and I’m lucky enough to have three great ones available by text . This ability to bounce ideas off of someone who understands both medicine and the limitations of low resource areas is a real gift to me. Thank you Federico, Kayt and Rachel.

Even in these areas of poor economic circumstances, the patients we see are deserving of high quality medical care. Lack of supplies, preferred medications or a variety of lab tests doesn’t excuse us from practicing the highest quality of care possible. It just requires that we search a little more deeply in our hearts and brains to come up with solutions. People don’t come to Loma de Luz because of two new temporary doctors being here. They have been coming here for years because of high quality compassionate care. And we can just relieve the current doctors so they can get away a bit or sleep at night, but the quality of care has to be maintained.

Some Thursday patients (this is written more for medical people and could be boring to anyone else):

Coming up: My quick bus trip to La Ceiba Saturday a.m.

June 13th, 2019 by Bryce Loder

Posted in Uncategorized|

I had either a mouse or a bear in my room last night. Didn’t do a lot of damage, but shared some of my food without permission and appeared to have made a detailed inspection of my belongings. Slept right through the invasion, and this morning there were neither bites nor blood to suggest that it had joined me in bed. I’m pretty certain that it wasn’t the same scorpion that stung my colleague, Talitha, the prior evening, because she smashed that critter with her bare foot. Ouch. I did have to cut out the sampled bits of mango and banana before I consumed them. And the howler monkeys were either mating or having a drunken party in the trees just outside my window at 4:15 a.m. Awakened only long enough to determine that I wasn’t invited to the party, and went right back to sleep. Hard rain yesterday, and temperature went down to 79°F/26°C. Felt like a nice winter night. Sleep was top notch.