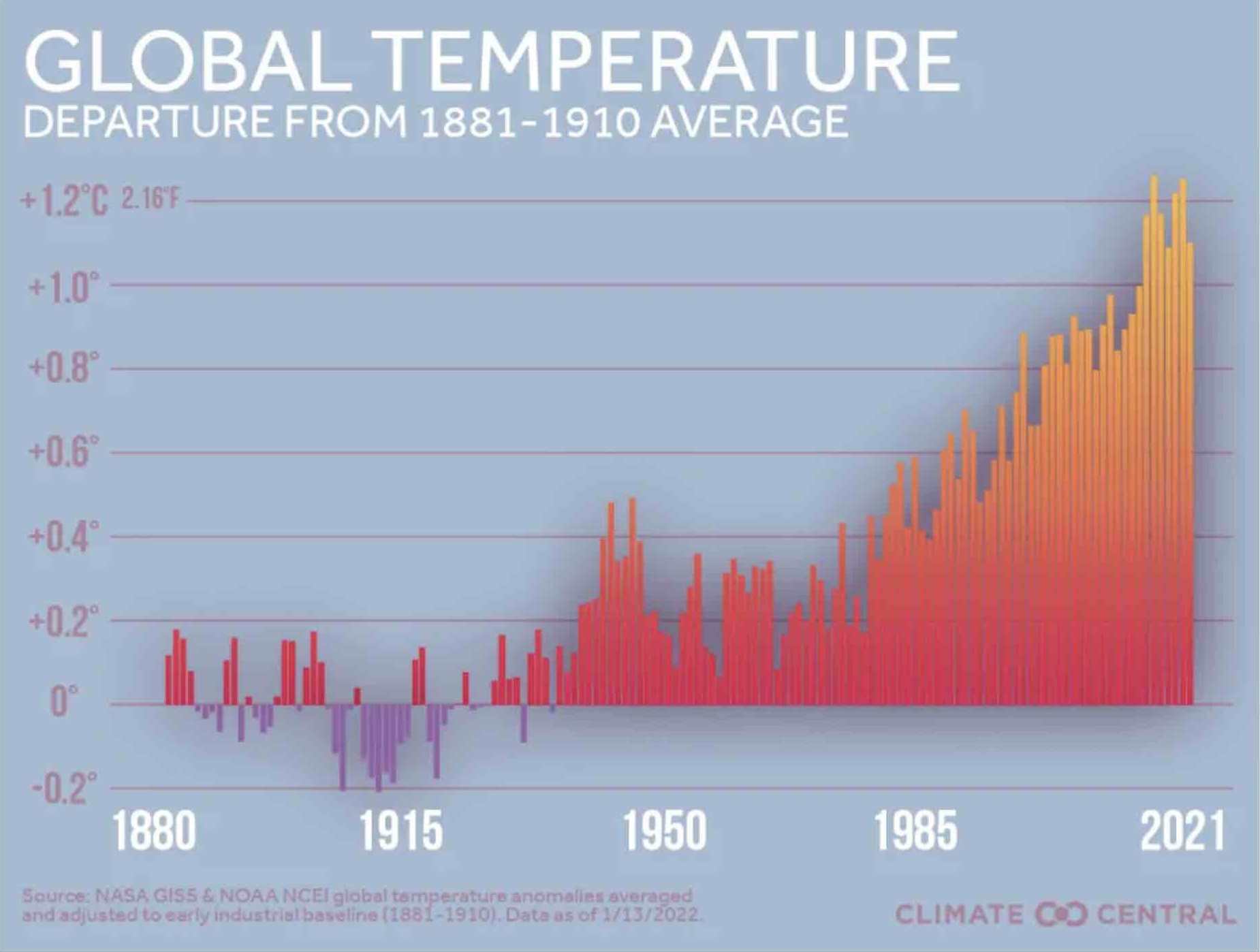

Temperature on the earth’s surface has been rising steadily for at least 140 years. Summer 2024 in the northern hemisphere is especially concerning, with mercury-popping thermostat measurements and record-breaking emergency department admissions. Understanding the impact of extreme heat on human health and implementing strategies to mitigate these risks is crucial – especially for the world’s most vulnerable people.

Temperature on the earth’s surface has been rising steadily for at least 140 years. Summer 2024 in the northern hemisphere is especially concerning, with mercury-popping thermostat measurements and record-breaking emergency department admissions. Understanding the impact of extreme heat on human health and implementing strategies to mitigate these risks is crucial – especially for the world’s most vulnerable people.

Health Impacts of Extreme Heat

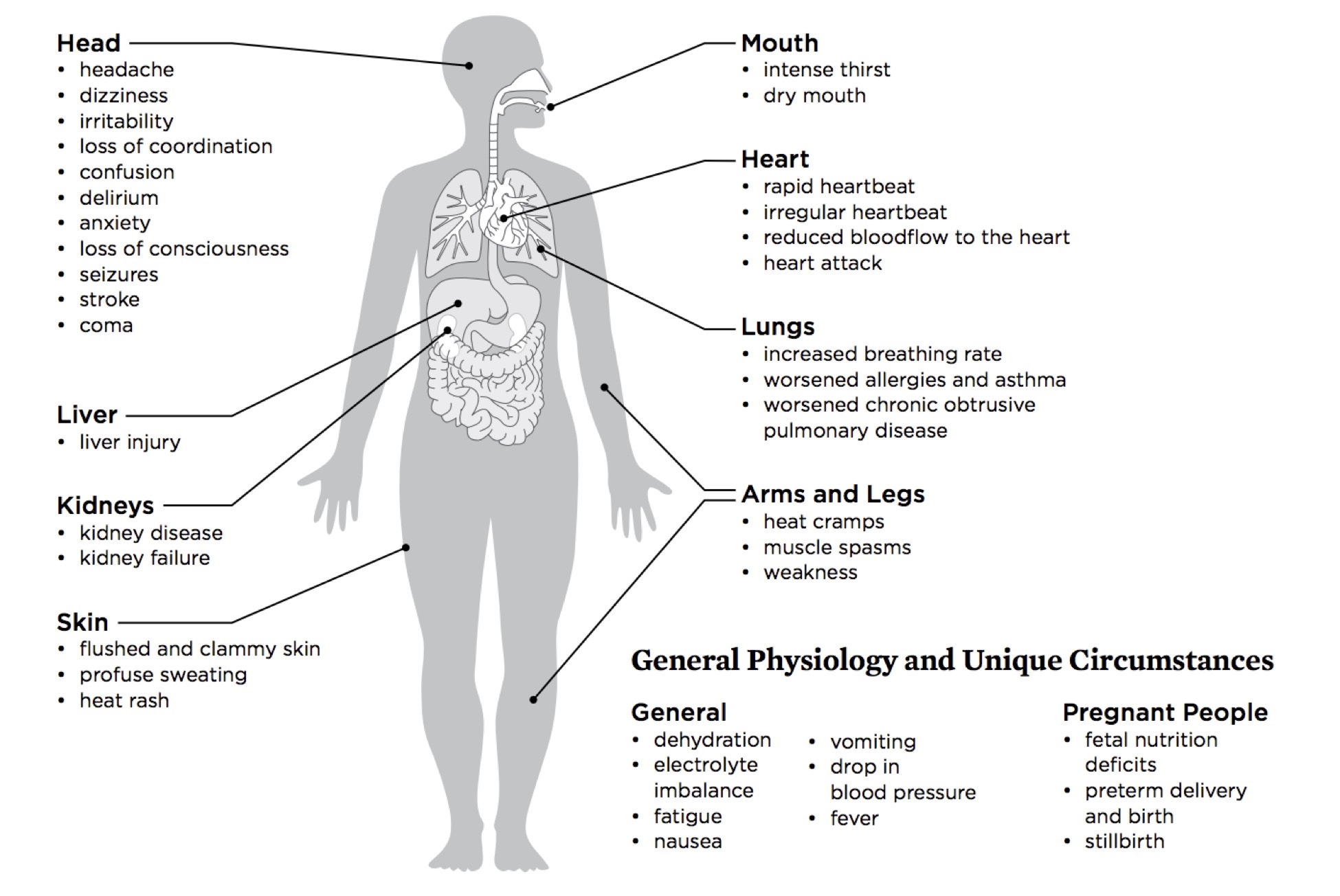

Extreme heat can have both direct and indirect effects on human health. Direct impacts include heat-related illnesses like heat exhaustion and heatstroke. Heat exhaustion is marked by symptoms like heavy sweating, weakness, dizziness, and nausea. Left untreated, it can progress to heatstroke, a life-threatening condition where the body’s temperature regulation fails, leading to rapid heartbeat, confusion, and potential organ damage.

The elderly, children, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. Older adults may have less ability to regulate body temperature, while children’s bodies heat up more quickly. People with chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory conditions, and diabetes also face higher risks during heatwaves. Some medications to treat these conditions can impair thermoregulation or reduce bodily hydration levels, further increasing vulnerability.

Extreme heat plus air pollutants is especially hazardous, often exacerbating respiratory problems like asthma and chronic lung disease. Mental health issues can also arise, as heatwaves have been associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and even aggression.

Extreme Heat and Vulnerable Communities

Extreme Heat and Vulnerable Communities

Low-income communities often lack access to air conditioning and other cooling resources, making them more susceptible to heat-related illnesses. Additionally, today’s sprawling urban areas, with their heat-absorbing concrete and limited green spaces, tend to experience higher temperatures than rural areas, a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect.

Environmental changes additionally play a role. Deforestation – whether urban or rural – reduces natural cooling and prevents the ability of trees to remove heat-absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. What’s more, access to life-saving safe drinking water is often constrained in the same low-income communities where it is most vital. Finally, some important infectious and contagious diseases are becoming more frequent particularly in low-income heat-strained communities. These include malaria, Dengue fever, Lyme disease, and West Nile virus.

Personal Mitigation Strategies

While this global phenomenon requires large-scale interventions – especially on the part of public health leaders, urban planners, and engineers – what can individuals do?

- Remain aware of the dangers associated with heat, adjusting our lifestyles to reduce exposure, increase hydration, exercise during cooler hours, and respond to signs of heat exhaustion in ourselves and our associates.

- Plant trees and cultivate green spaces on our lands to decreased heat retention close to home, and to a smaller extent, in our broader locales.

- Take precautions against high-risk contagious diseases, most often through personal protective clothing, insect repellents, and protective doors and screens on our homes.

Extreme heat and human health are closely connected. The steady march rise in global temperature is also associated with increasing data on heat-related illness. This association is especially concerning in the very communities who have the least resources to respond. While worldwide solutions are being explored, we each are wise to take individual action to protect ourselves and our loved ones.