With no measles nearby, the vaccine is not necessary.

The Spanish flu began in Spain.

Healthy adults must drink eight glasses of water per day.

You can catch a cold by being cold.

Drinking the beverage Vitamin Water will make you healthy.

What do each of these statements have in common? First, they are all untrue. Second, they continue to be believed.

Let’s look a little deeper. How do we know these statements are untrue? Because of epidemiology. Epi, short for epidemiology, is the scholarly study of health and influences upon health for the purpose of protecting the well-being of populations. Epi draws from multiple disciplines including psychology, statistics, medicine, genetics, and more. Epidemiology guided experiments, for example, have objectively demonstrated that there exists no health difference between people who drink Vitamin Water in those who don’t; between adults who drink six or 10 glasses of water per day.

Yet why do these statements continue to be believed? Confidence in health misinformation has multiple origins that include dismissive behavior by healthcare professionals, personal association with communities who confirm suspicions, and occasional research-based updates that reverse earlier recommendations. Often the loudest health misinformation voices have an ulterior motive like selling a product, persecuting a group of people, or protecting their own brand or reputation.

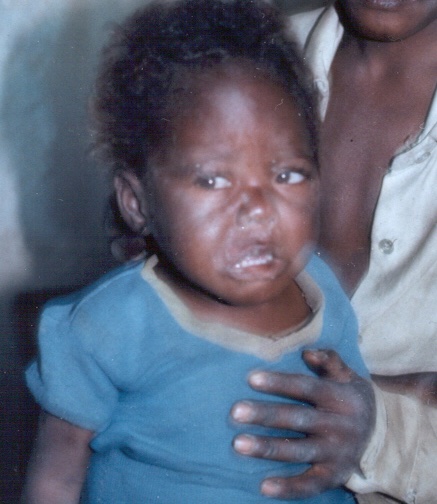

What is the greatest danger of epidemiology? I witnessed it firsthand: For two years in the 1990s I served the nation of Angola, southern Africa, during their Civil War. Few children in that nation of 11 million received measles vaccine, and almost daily I cared for children, including this one. Notice the red spots on her hairline and the crusting around her nose? She’s also coughing, and her temperature is 104°/ 40°C. Classic measles infection! Many of these children are malnourished to begin with, and 1 in 20 will go on to develop pneumonia – the most common cause of death from measles in children.

What is the greatest danger of epidemiology? I witnessed it firsthand: For two years in the 1990s I served the nation of Angola, southern Africa, during their Civil War. Few children in that nation of 11 million received measles vaccine, and almost daily I cared for children, including this one. Notice the red spots on her hairline and the crusting around her nose? She’s also coughing, and her temperature is 104°/ 40°C. Classic measles infection! Many of these children are malnourished to begin with, and 1 in 20 will go on to develop pneumonia – the most common cause of death from measles in children.

Back in the US, I reviewed the multiple epidemiological studies demonstrating that one dose of measles vaccine is 93% effective in preventing the disease. Two doses are 97% effective. But with measles rarely reported, many American parents decline vaccinating their children – even though measles is highly contagious and easily imported from elsewhere. Unsurprisingly, easily preventable measles cases in America are surging. In 2019, more than 1,200 cases of measles were reported – the highest number in decades.

The great danger of epidemiology is to ignore what epidemiology reveals. The peril associated with this field is to embrace the counsel of those whose positions are unsubstantiated and often principally motivated by self-interest.

This summer, INMED is offering our core Epidemiology Course. Taught by Joe LeMaster, veteran of 11 year’s service in Nepal and graduate of the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, this learning experience is especially tailored for low-income and cross-cultural communities to enjoy the benefit of epidemiology.