It’s February. Christmas festivities are long past. Those New Year’s resolutions that briefly infused inspiration are already becoming forgotten. The short, often gray days of winter layer a sense of gloom, even cynicism, over our moods. Valentine’s day is approaching, whose reminder that we ought all to be “in love” often makes it the holiday people love to hate. Then come the bills in the mail. Those credit cards from Christmas, property taxes, and, oh yes, it’s time to start preparing year-end income tax returns, too.

No wonder people become depressed in February! Suicide attempts climb. Mental health facilities fill up. Counselors start overbooking their schedules. And, oh, observe the soaring number of prescriptions filled Prozac, Ativan and Elavil! Justifiably, people want a cure from for the wintertime blues. But counselors start at $75 per hour. Medications take weeks to begin working. And when we’re honest about it, who really wants to be in therapy?

Let’s consider a “new” solution: selfless giving.

Selfless giving is a cure for melancholy and depression that is rooted in generosity towards others. But its therapeutic results don’t stop there. In his landmark book, Give To Live, Douglas M. Lawson, PhD, reveals the findings of extensive research on the health effects of giving. It didn’t matter much what people gave away. Gifts of time, money, or material possessions all had a similar affects. The factor that mattered most was the frequency and the attitude with which people gave. Those who made giving a regular part of their lives experienced a longer life expectancy, increased immunity, improved blood circulation, better sleep, and significantly less depression.

One of the most visible examples of therapeutic giving’s results can be seen in the life of Andrew Carnegie. This impoverished Scottish immigrant worked his way up to establishing the Pennsylvania steel industry in 1865, and by 1900 sold it for $480 million. But Carnegie hit a snag along the way. He became plagued by despair and paralyzed by physical illnesses linked to depression. His solution? Give away his wealth!

In 1889 Carnegie wrote The Gospel of Wealth, in which he stated that all personal wealth beyond what was required by one’s family should be regarded as a trust fund to benefit the community. Carnegie added, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” Carnegie established educational organizations that, among other objectives, founded 2,509 libraries around the world. Carnegie also became known as one of the most exemplary and joyous philanthropists of his day.

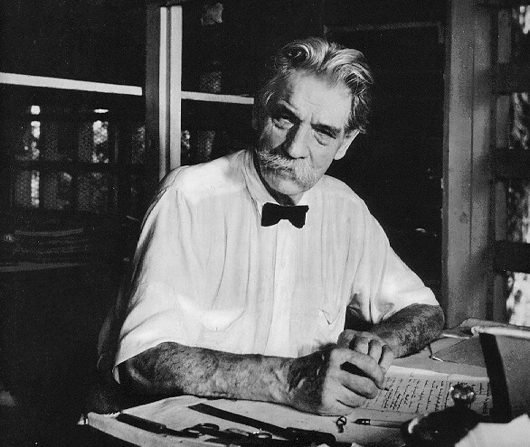

Few of us have access to the material wealth of Carnegie, but the power of giving is no less inspirational. For me personally, the example of Albert Schweitzer is most compelling. Schweitzer was not particularly blessed with financial resources. But he was a very wise man. By age thirty, Schweitzer had completed three PhD degrees in philosophy, music and theology. He had also become a popular author, whose books were widely read in Europe and America. But still, Schweitzer found his life incomplete.

In his autobiography, Out Of My Life And Thought, Albert Schweitzer wrote, “It struck me as inconceivable that I should be allowed to lead such a happy life while I saw so many people around me struggling with sorrow and suffering… I had already tried many times to find the meaning that lay hidden in the saying of Jesus: ‘Whosoever would save his life shall lose it, and whosoever shall lose his life for My sake and the Gospel shall save it.’ Now I had found the answer.”

Schweitzer resolved to leave the university where he taught, and to instead become a ‘jungle doctor’ and establish a hospital in equatorial Africa. His friends and relatives reproached him over the folly of such an idea. Why waste such a glorious, gifted career to serve faceless Africans on another continent? Schweitzer prevailed over their protests and entered medical school in Germany. Next, using the funds earned from his own book royalties and personal appearances, Schweitzer moved to Gabon in 1913 where he began caring for ill Africans and constructing a hospital. Most of the rest of his life was devoted to the health care of the people in the region.

Far away but not forgotten, Schweitzer welcomed journalists to Gabon, whose reporting on his ministry inspired an entire new generation of medical missionaries. In 1952 Schweitzer received the Nobel Peace Prize, and used the money to further expand the hospital and leprosy center. In 1955 Queen Elizabeth II awarded Schweitzer the Order of Merit, Britain’s highest civilian honor. And of the personal, emotional impact of his ministry, Schweitzer wrote, “It amazed me to experience how serving the love preached by Jesus sweep me into a wonderful new course of life!”

As we ourselves pass through life’s valleys and turmoil, where shall we turn for relief? Indeed, some people benefit enormously from counseling or medication. But we also do well to consider adding the “natural,” timeless remedy of therapeutic giving. This does not necessarily mean a radical move to Africa. Rather, begin with simple steps towards becoming more generous. Give to a charity. Sponsor a child. Coach a team. Volunteer at a hospital. Offer your skills to a non-profit organization. Give for the sheer sake of giving, and without expectation of any external reward. I trust that you will eventually resonate with Schweitzer’s observation: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.”